If you thought that was it, that my last post was enough of an emotional roller coaster, you (and I) were wrong. I thought that, after making it through the first stage (over the Anzob Pass to Dushanbe) and overcoming one major emotional struggle (my irrational fears), things would get easier from here. And, at first, it seemed like they would, but soon enough, new challenges hit.

After turning off the main (paved) highway up into the mountains toward our next high pass—along the “North Route” to Qal’ai Khumb—the road got extremely bad. We knew the road would be tough, but we didn’t expect the extent of it. We were covered in dust, feeling like we weren’t moving at all. Gravel would have been a relief; instead, the remnants of old pavement made it nearly impossible to maintain any consistent speed.

Although, on average, the road only climbed gradually along a river, it repeatedly climbed steeply only to dip back down to the river on the other side—creeping slowly up, then because of the bad road conditions almost as slowly down. Before Tajikistan, we rarely cycled slower than 6 km/h, even on steep stretches, and going any slower always made me frustrated. Here, in Tajikistan, <5 km/h became the new normal—and it was nerve wrecking.

Thomas and Tim used to convince me that my bike would do its job; I just needed to trust it and let go of the brakes. But apparently, this was finally “too much.” First, we discovered that a thread holding my lowrider is ruined (Thomas fixed it with superglue, which, surprisingly, held), then I got my first flat tire, and then a second, and a third… they just kept coming. We quickly ran out of intact tubes and nearly exhausted our supply of (functional) patches. Worst of all, at first, I couldn’t even fix my own tubes—not because I didn’t know how, but because I lacked the strength. Or so I believed, because when I was finally on my own with no other choice, I managed.

After all the trust I’d built in my bike, I felt like I lost it in just a few days. Thomas tried to convince me that tires and racks weren’t “my bike,” but I didn’t see the difference—either my bike rides, or it doesn’t, and lately, it had been out of order “more often than not.” Every day, we seemed to fall short of our goals, barely covering a third of what we’d planned, despite daily adjustments to our plans and lowering our expectations. Even though I’d mostly overcome my irrational worries about having enough supplies, my feeling of not being ready or good enough for this still—or perhaps increasingly—flourished.

We made it through, though not without damage. We both felt increasingly alone, misunderstood, and unappreciated. Finally, we had reached the Pamirs—one of the places that had inspired us to leave home so many months ago—yet now we were questioning why we were here and whether we still wanted to continue. Or maybe more accurately, whether the other one still wanted to go on.

Of course, we were doing this together, and neither of us would have started this journey this year if we weren’t doing it together. And yet, Thomas could totally do this on his own whereas I couldn’t—or at least wouldn’t. Our route on the app was created on July 25, 2021. It had been modified many times since, but Thomas’ dream of coming here took root long before I even knew the Pamirs existed. On the other hand, Thomas had said he was done with “long” cycling journeys until I suggested to do another one (my first). During the trip, Thomas has often mentioned that he always loses the spark for traveling after two months. So, who’s accompanying whom? And why? And still?

Being weaker, slower, and closer to my limit 99% of the time, I sometimes forget that Thomas also has his struggles and I probably needed a wake-up call to get out of my “me-me-me” mindset. Realizing what I could lose brought back my gratitude for what I have. And so, after reaffirming that, even though things were pretty rough at that moment, we wanted to continue—this journey and beyond—we finally started heading uphill again.

We met an Italian and a Spanish motorcyclist in Qal’ai Khumb who were traveling together. The Italian always says, “It is part of the journey” when something unpleasant happens. In those early days in Tajikistan and the Pamirs, I often wished that all these external and internal struggles weren’t part of our journey. But they were—“it is all part of the journey”—and probably for a good reason. At the very least, knowing that we didn’t give up when things got tough and that we found a way through together built a deeper trust in us—one that I value far more than my wish for an easy ride.

Anecdotes

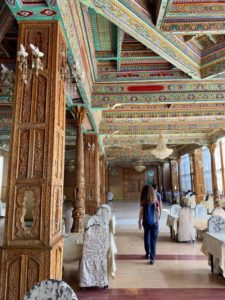

Dushanbe: Free travel tour guide: “This is one of the oldest buildings in Dushanbe.”

Me: “How old is this building?”

Guide: “About 50 years old. You are very lucky to still see this old teahouse over there. Take pictures! Take pictures! They’ve built a new government building next to it. The teahouse will be gone next month.”

What a difference compared to the rest of the country!

Obigarm: We thought we could go a bit further that day (94 km, 1400 m of climbing) to stay at one of the three decent-looking hotels in Obigarm, only to find that all were closed except one we’d initially passed, deciding it looked too bad to stay in. Unfortunately, my tire went flat (the first of many to come) from a metal piece I’d “collected” while searching through the town, and it was already dark, so we had little choice but to take that place.

They wanted to charge us double the local rate, the shower wasn’t working (though there was a public bath next door that we had to pay extra), the room looked as if it hadn’t been cleaned in a year, and only a thin stream of dirty water trickled from the bathroom sink. But the worst part was the toilet. Thomas suggested I do what signs sometimes say not to do—stand on the (sitting) toilet—which I would have tried if I hadn’t judged the risk of slipping too high. My other option was to use one of the other room’s toilets I’d seen when I complained about the filth, and the “manager” showed me other rooms. None were any better, but a few had less offensive toilets. However, I couldn’t remember which rooms he’d shown me, and I worried about accidentally barging into an occupied one. Finally, Thomas dug out disinfectant wipes from the bottom of one of his bags—an, until that evening, unused goodbye gift from his mother, which turned out to be my night-saver.

Tavildara: After that night, I thought I’d never stay in a hotel here again. But two days later, after what felt like endless stretches of broken pavement and gravel roads, covered in dust from head to toe, we rolled into Tavildara. The officer at the security checkpoint just before the bridge into town gifted us two pears—a welcome addition to our breakfast, as we planned to camp behind the sports field (marked on iOverlander).

We crossed the bridge, and it was like a mirage! The road was paved, flowers adorned the roundabout, there was a shop selling fresh produce (and more pears), and a massive brand-new hotel with luxurious rooms. Thomas, thankfully, chose the larger one, and it felt like a suite!

And so, within two days, we stayed in both the worst and best accommodations of our month in Tajikistan. The only thing missing in town was a restaurant, so we ended up cooking in our suite… which only made us appreciate the hotel’s luxury even more.

Qal’ai Khumb: “What did your parents say?” was Sonja’s first question after the guys cycled ahead of us. We’d just met them not five minutes ago, and apparently, we were the first cyclists they’d come across in months. Then she continued, “If it’s not too personal for you, how do you handle your menstruation?” Timing, rest days, irregular cycles, skin irritations, ovulation… we happily chatted along.

Apparently, both Thomas and her partner had, at some point, asked in surprise if we experience pre-menstrual mood swings at home, too. We laughed—yes and no. We have them much less, but mostly, at home, we have our balancing mechanisms and can retreat to solitude if needed. Here, our bodies need to work like clockwork, and we’re “exposed” to each other 24/7, so the guys feel it more—but so do we.

Qal’ai Khumb to Rushon: The entire road, about 160 km, was one big construction site. We were repeatedly warned about how incredibly awful and extremely dusty it would be, so we expected the worst—so much so that I kept asking myself when the really terrible parts would begin. Yes, the road was often rough, but some sections were newly paved, and the rest wasn’t as bad as the North Route to Qal’ai Khumb (except for the short stretches where active construction forced us to push our bikes over rocks or through deep dust and sand piles). Yes, it was dusty, but not as dusty as before Tavildara on the North Route. We’d expected the worst, and maybe it helped that we had a beautiful hike to look forward to, but this time, we were pleasantly surprised!

Leave a Reply