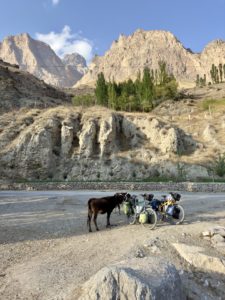

“Welcome to our country, miss.” With these words and the friendliest smile of any border police officer I had encountered so far, I got my passport back with the entry stamp to Tajikistan. Everyone greeted us warmly from the side of the road, and children came running into the middle of the road from the other side of the fields, screaming “hello” and trying to give high fives—even as we sped down the mountain at 40 km/h…

We had waited so long for this moment, and suddenly—perhaps all too quickly—we were here in Tajikistan, already heading towards our first >3000 meter pass (Anzob Pass). Stumbling into this new adventure, I felt suddenly overwhelmed. After a month of almost no cycling and the only flat terrain of Uzbekistan, I felt unfit, and my self-doubts were on autopilot.

On top of that, we quickly reached high altitudes, and my system was in permanent alarm mode. The road got worse and worse, the slopes were steep, and my wheels sometimes lost grip. Whenever I had to pedal hard, my already high pulse escalated as if I were having a panic attack. My mind tried to make sense of my body’s reaction, coming up with all sorts of reasons why “fear” was a reasonable emotion—and believe me, it found many! Were we going to manage this? Would we have enough water? Enough food?

When faced with a challenge, I tend to increase security margins, while Thomas optimizes—a difference that usually balances well but suddenly felt like a threat to me. For example, when I saw the first water stream in a long time, shortly before we wanted to take a break, and knowing we didn’t have enough water reserves (a worry that had occupied my mind for the past hour), I thought, “Great, I can at least alleviate one of my worries!” But Thomas thought, “If there’s a stream here, there’ll be another one just up ahead after the turn, so we don’t need to carry water from here,” and passed the stream—and the next one—with our water bag just out of my reach a few meters in front of me, while my mind kept racing, asking why “he was doing this to me.”

There were plenty of water streams, and the people were incredibly friendly—they would never have let us go hungry. However, even though I knew my worries were unreasonable, I couldn’t calm my racing mind. The more I panicked, the less seriously Thomas took my concerns. Understandably so, as my usually rational mind had mostly disappeared, and I had turned into a critical beast I didn’t recognize myself. But this only increased my agony, worry, and stress. It wasn’t until much later, after explicitly asking Thomas for support—to stop fighting my worries and instead give me the space I needed to “solve” my mostly imagined problems—that I managed to break free from my panic spiral (thank you, Thomas).

On our ascent to the pass, we decided to stop earlier than planned when a woman invited us to her home in Anzob village. This meant we had 1,700 meters of climbing and 105 km to cover the next day to reach Dushanbe, Tajikistan’s capital. When I worried about the distance and the strong headwind predicted for the next day, Thomas reassured me, saying I’d just have to ride in his slipstream.

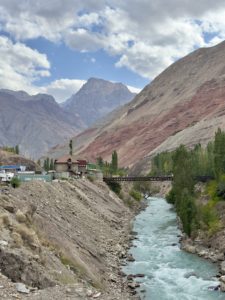

The pass was steep, and the road was bad (the pass has been closed to cars for years and isn’t maintained), so we didn’t start our 86 km descent until around 2 p.m. For the first stretch, the wind wasn’t a problem because the poor road conditions were the limiting factor. Then, we finally rejoined the road for cars coming through the Anzob Tunnel (a tunnel that was never completed and lacks lighting, ventilation, and drainage) at 4 p.m. with still 70 km to go.

I saw Thomas glance into his rearview mirror and slow down just enough for me to catch up—my signal to get into his slipstream. I’ve learned to love riding in Thomas’ slipstream. Handing over my view of the road ahead (while still keeping an eye on traffic), I follow his every movement—trusting that I’ll be safe and that there’s a reason for everything, even if I don’t see it yet. He swerves to the right, I swerve to the right—and only later do I see, if at all and too late to react, the pothole, stone, or whatever else caused the swerve. This feeling of trust and being completely in sync is beautiful but can also lead to some dumb reactions on my part. For instance, when Thomas slows down and swerves to the right for me to come alongside him, I—following blindly—slow down and swerve to the right just behind him… Why? Oops!

Riding slipstream on flat terrain is one thing, but going downhill on uneven roads without being able to see what’s ahead is quite different. What had sounded good the day before suddenly felt scarier than expected. Sometimes, I would ride slightly off-center to get a glimpse of the bumps ahead, but this wasn’t often possible due to traffic or tunnels. The tunnels had dim lighting, if any, and I was blinded by the reflectors on Thomas’ bicycle. So I rode as closely as possible, following Thomas’ path and watching his bike jump up and down to predict how mine would react.

I must have used up all my adrenaline over the past few days and the climb because I was completely at peace, knowing that, objectively speaking, this was more dangerous than any of the things that had triggered my near panic attacks on the way up. It probably helped that we were now at a lower altitude than the past three nights, and there wasn’t much that could have possibly pushed my heart rate out of its comfort zone. Eventually, we rolled into the brand-new, brightly lit capital—a stark contrast to both the mountains and the history-rich cities of Uzbekistan.

Anecdotes

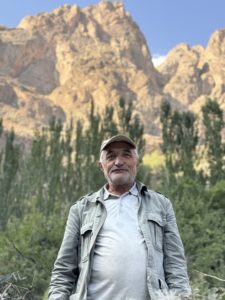

Anzob Pass: At the summit, 3,375 meters above sea level, in the middle of this “impassable” road, lives a meteorologist who has been sending hourly weather updates year-round for the past 40 years. When Thomas prepared for this trip more than half a year ago, he read on iOverlander (an app by and for overlanders) that this man is always excited to see and invite people in, and that he had been looking for a rechargeable torch. Thomas almost packed his old headlamp for him but figured he must have gotten one by the time we arrived.

As expected, we were invited in for tea (and lunch, though we didn’t have time to stay), and we had a simple, slow conversation using Google Translate. People here speak in such flowery expressions that the translation often comes out almost devoid of meaning. Just before leaving, the meteorologist asked us, in a roundabout and convoluted way, whether we had a rechargeable lamp—a question we might not have understood if we hadn’t already known it. How could it be that he still hadn’t gotten a lamp? After some thought, we decided to give him one of our fancy, super-light, USB-C rechargeable headlamps—probably the most modern item in this old-fashioned weather station.

Writing this a few weeks later, it still makes me happy remembering how delighted he was. I feel privileged to have had the chance to gift him our lamp, especially as we came at the very end of the season and several other cyclists with rechargeable headlamps must have passed through before us this year.

Leave a Reply