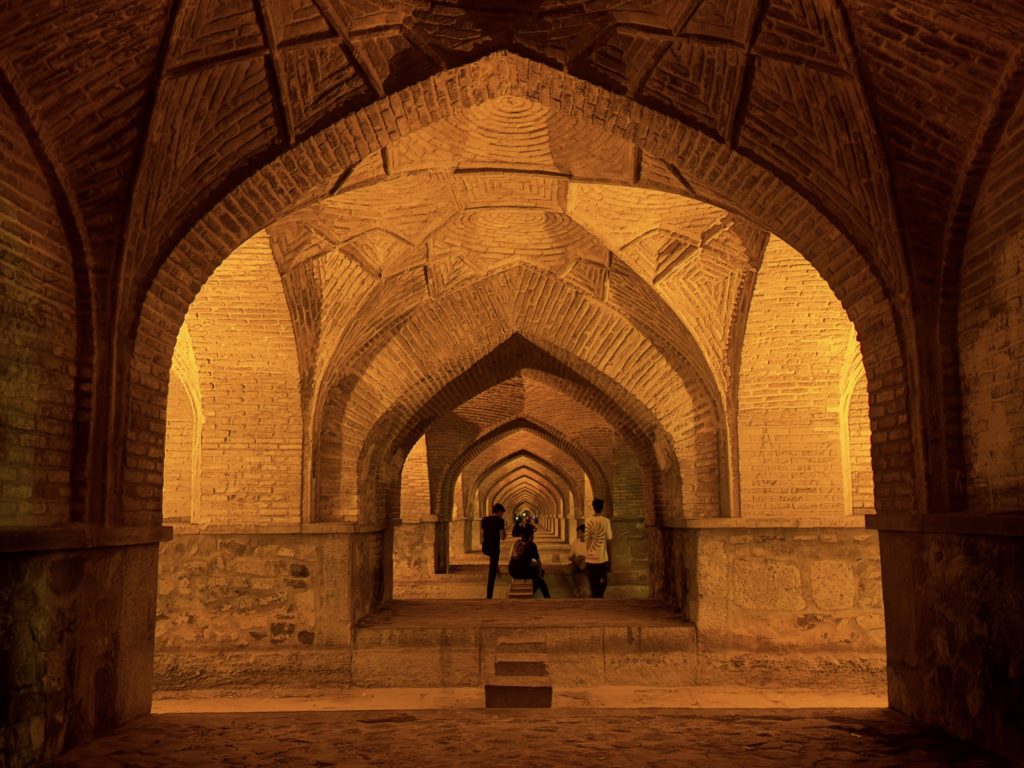

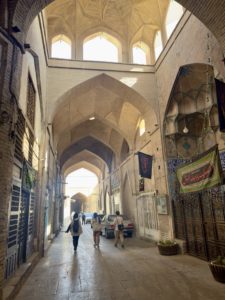

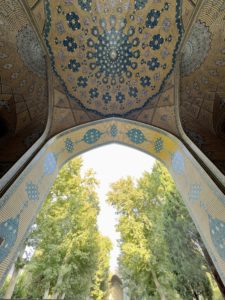

Unlike the mountainous, cooler regions of the northwest, central Iran boasts a different character—its landscapes are arid, and the cities are filled with stunning examples of Persian architecture. From the intricate tilework of Isfahan’s mosques to the wind-catching towers and adobe buildings of Yazd, we were immersed in centuries-old craftsmanship that showcases the country’s rich heritage. On the bike, our backs are usually bent forward, but here in the cities, our necks craned back to admire the beautifully decorated ceilings.

Since visiting Khalkhal, the coldest place in Iran, we’ve been asked repeatedly how we can possibly cycle in this heat and if we know how much hotter it will get where we’re heading: “Here, it’s still okay, but at the Caspian Sea, it’s much hotter,” or “It’s still okay now, but wait until you’re in Tehran, it’s so much hotter there!” „…but wait until you are in Esfahan, it’s so much hotter!“ And then: “Esfahan is hot, but Yazd? Yazd is so much hotter! Even the wind feels like a hairdryer blowing at you!”

Yes, we knew. But we thought it would be fine and ventured into the desert, cycling from Esfahan to Yazd over three days, with a stop in Varzaneh to see the sand dunes. And it was fine. In fact, Thomas still thinks the 35°C in Croatia was the worst—hot, humid, and we weren’t used to it yet. I barely remember the heat in Croatia but think the Caspian Sea was the worst—exactly where everyone told us it would be the coolest (except for Khalkhal). According to the thermometer, it was indeed cooler, but the humidity was high. I was soaked in sweat beneath my long clothes without doing anything, and cycling only made it worse. The desert was different. It was extremely hot—the bike computer read 55°C in the sun—but it was flat, and as long as we kept cycling, the wind helped cool us down enough to make the heat easily bearable. Just our mouths were very dry, despite constantly drinking.

On our last day before reaching Yazd, we had cycled about 50 kilometers through the desert. It was extremely hot, and we were thirsty. We still had water, but it tasted like warm tea without flavor, and we craved something cold. To our great surprise, we were allowed into the industrial area where the only shop within a 30 km radius was located—and it was actually open. They were so excited to see us in the middle of nowhere that they offered us everything: a bathroom, a place to sleep, lunch, and, of course, a cold drink—but first things first. We had to engage in small talk, answer questions about where we were from and where we were headed, and—very importantly—pose for pictures with all the shop‘s employees. Then, of course, we had to sign the guestbook and praise their hospitality (wait, where was our cold drink…?), and marvel at all the other cyclists who had found this shop before us. Finally, the cold drink—and another cold drink—made up for it all. The slightly forced smile I had posed with earlier turned into a very genuine one as we gave our thanks and farewells.

People here are so friendly and welcoming that the most “unfriendly” thing might be their sheer enthusiasm. They’ll stop us in the middle of the road to invite us for lunch, go out of their way to help with any potential problem—even if there isn’t one—and gift us more food than we can eat. They welcome us with open arms, telling us how much they love us, and then ask immediately, “How do you like Iran? How are the people?” And though we sometimes feel almost “tricked” into saying it, it’s nonetheless true: Iranians have been the most welcoming, helpful, and generous people we’ve encountered on our journey so far.

Anecdotes

Esfahan: I’m not sure I’ve ever gone clothes shopping specifically for a party before (except for balls and weddings). But in Esfahan, I followed Sarah (who we met again here with Tobi) into a shop and came out with a new green dress—for the party the next day (and many other city occasions in the future). I finally had something new to wear, and what a highlight that was! After three and a half months with a very limited wardrobe, and just two tops for the past two and a half weeks, I now had something fresh. It was probably the cheapest item of clothing I own, but it was new—and a dress, no less—making it feel both exotic and luxurious.

Afterward, we crossed a long bridge over a wide, dry riverbed. In the middle of the bridge, we stumbled upon a group of men playing music and watched the crowd that had gathered around them, swaying and singing along. Then, without warning, the musicians abruptly jumped up and ran, probably alerted by a sign we hadn’t noticed. The crowd, suddenly aimless, slowly dispersed, and we, too, made our way to the other side of the bridge, where the police casually marked their presence.

Varzaneh: And then it hit me!

- We had a long day through the desert the day before (105 km in 50°C heat).

- From all the hijab conformity, I detest wearing long pants over my already uncomfortable cycling shorts the most (don’t tell my butt, it’s grateful for the extra padding). Thomas, who isn’t obligated to, had stopped wearing long pants for cycling by our third day in Iran (no judgement, just emphasizing how annoying it is).

- I was nearly pushed off the road by two guys on a motorbike heading straight toward me from the opposite lane for no apparent reason.

- We arrived in Varzaneh after sunset, only to find the hotel we had booked (and received a confirmation email for) was closed.

- Trying to find dinner during a citywide power outage didn’t feel very welcoming.

- Masih Alinejad’s audiobook, „The Wind in My Hair—My Fight for Freedom in Modern Iran“, was still fresh in my mind, along with the struggles of thousands of women against compulsory hijab in her “My Stealthy Freedom” campaign, and the acid attacks on women in Isfahan, the city we had just left.

- I knew my 30-percentile strategy wasn’t going to work this day. During our evening stroll through the city the day before, we barely saw any women, and those we did see were all covered in black or, a local tradition, white chadors—or what looked like being wrapped in a bedsheet (which would at least technically be possible, as the hotel we found as an alternative provided bedsheets for sleeping).

- Boys, on the other hand, seem to learn to drive motorcycles in kindergarten, judging by the size of the boys that shot out of dark alleyways in the evening.

- I had a slight headache.

- I slept well until early morning, but then I couldn’t really fall back asleep because of the heat.

- It was hot—way too hot—but I was too lazy and too “considerate” to get up and turn on the air conditioning.

- I was soaked in sweat and dreading having to put on all my layers to go into the courtyard for breakfast, where the “ugly” man—another guest, or whoever he was—might be lounging again, bare-bellied, like the evening before.

I wanted to scream, but instead, I cried—

And eventually got dressed.

None of the men in the courtyard (or anyone else, for that matter) had ever looked at me disapprovingly. That “ugly” man had even covered his belly when he saw me enter the courtyard yesterday. Thomas is always compassionate and never told me not to turn on the air conditioner. And have you ever seen the Milky Way from within a city? Still, it can be exhausting to constantly adapt and redefine myself—deciding how I want to be, behave, and respond to my constantly changing surroundings. But in the end, it’s up to me to decide how to view the world around me, what to focus on, and how to respond. So, I stepped out from behind the heavy curtains that shielded our private life into the courtyard and joined Thomas at the breakfast table, where the guesthouse owner served us a delicious meal, and the “ugly” man greeted me kindly.

That evening, after our visit to the desert, I found myself cooking dinner for the next day, alone in the open kitchen in the public courtyard, wearing a long, loose dress with my hair wild and uncovered. It’s amazing how even cooking can feel like an act of defiance. And once again, the “ugly” man smiled at me kindly and offered to share his drink with us.

Yazd: It was another one of those moments where things worked out, just not in the way we expected. Once again, we were searching for a falafel place with good reviews on Google Maps, but this time it turned out to be closed. So were the two other falafel spots nearby. There was one more place that supposedly served falafel, but all we saw was meat—lots of it, in all kinds of large, very meaty-looking forms. When we asked, they confirmed what we suspected: no falafel. However, one of the workers mentioned another place (the one that was closed) and yet another one. Due to the language barrier, he stopped what he was doing and walked us to this “other place.”

When we arrived, there was something about the people there that felt… off, though we couldn’t quite put our finger on it. After some back-and-forth between them, they gestured for us to sit down and choose our drinks. Not long after, our falafels appeared—not from their kitchen, but through the main door. Wherever they came from, they were pretty good, and we happily continued with our sightseeing afterwards.

Mashhad: I sat pressed against a wall, listening to the Friday prayers and watching women pray, read, cry, and take pictures of their little children dressed in cute looking chadors. Beside me, the female guide who had been assigned to me—after I’d spent half an hour in a security office without explanation—crouched behind me. She explained that all the decorations in the courtyards of Mashhad’s shrine complex are only in blue and yellow; no red is allowed because it’s considered aggressive.

“What about all the red lights?” I asked.

She winced. “No! No red,” she insisted. I raised an eyebrow and looked around. All the balconies on the second floor all around the court yard were flooded with red lights. “There?” I asked. She hesitated, then explained, “That’s because of the martyrs’ death. For two months, they have red lights.”

I nodded, once again feeling a wave of relief that the security officers hadn’t decided to inspect my sketchbook, where I’d sketched something after my meltdown that morning in Varzaneh. At the same time, I couldn’t help but laugh at my own absurd worry—it was just a silly drawing capturing a fleeting emotion of mine… no?

Finally, we were able to leave, but there were still more courtyards to see. My guide hurried me through them, worried I might get lost, constantly reminding me that we had to behave well in this sacred place. She repeatedly readjusted her headscarf, which looked so firmly fixed that I couldn’t imagine anything moving it. By this point, I was exhausted and just wanted to get out and meet Thomas for dinner. He had been free to explore the complex by himself and had already seen everything—including the shrine itself—a part of the complex my guide had barely mentioned.

Every time I tried to tell her that Thomas was waiting, she bombarded me with more dates, historical figures, or answers to questions I hadn’t asked. She insisted that it was their duty to show tourists all the courtyards, every single one. I tried again, and suddenly, something clicked. “Oh, husband is waiting! Husband is waiting!” she exclaimed. In an instant, the remaining two courtyards were forgotten, and before I realized what was happening, we were outside the complex, and with her job seemingly finished, she disappeared into the night.

Taxi: Due to the heat, but mostly to save time, we had planned to rely on buses for the longer stretches of our journey through Iran. However, as I mentioned before, most of the buses were in Iraq for Arba’in. So, instead, we took taxis: from the Caspian Sea to Tehran, from Tehran to Esfahan, from Yazd to Mashhad, and finally from Mashhad to Bajgiran, at the Turkmenistan border—amounting to nearly 2,000 km of taxi rides!

When I think about the 16 CHF I used to pay in Zurich for a 5 km ride home after a night out 15 years ago, 2,000 km in a taxi sounds impossible. Fortunately, we weren’t in Switzerland, and the total for all those taxi rides came to “only” 340 Euros—a fortune in Iran, and probably about half of our total expenses for the entire month. But worse than the cost was the experience of being in a car for such long stretches. At least we had something to look forward to: cycling again! Just three more days of non-cycling in Turkmenistan, and we’d finally be back in the saddle in Uzbekistan.

Leave a Reply