After two months of cycling as a duo, we left Kars as a trio. Thomas’ friend, Tim, flew to Kars in the far corner of Turkey to join us on our detour through Georgia and Armenia. After weeks of heat and sunshine, it poured rain the day we met Tim in Kars. Luckily, the sky “emptied itself,” and it was mostly dry when we left Kars together the next day.

After two months of cycling just behind Thomas in his lee for large parts of our rides, we now rode leisurely next to each other, happily babbling along and talking about past and present experiences, and, of course, some technical stuff such as the new railway beside us. The roads towards Georgia were new, wide, and had little traffic, so we mostly fit next to each other on the street’s shoulder. Finally, we had someone to tell all our stories to that we had collected over the past two months. While I was listening to some of those stories from Thomas, I realized how much I enjoyed hearing him talk about something I already knew. It feels odd to tell these stories to each other, but listening to Thomas tell them to Tim—reviving the moment and feeling curious about his slightly different take on it—I find it a pity that we don’t do this more often when it’s just the two of us.

Thomas had by far the most experience in cycle touring and took on a lot of responsibility, but by now, we had found our rhythm together. Tim dove in headfirst, going from never having done more than a few hours of cycling to borrowing Thomas‘ old bicycle and joining us for two and a half weeks through three foreign countries in rather remote territories. Thomas had traveled with both of us individually before, but Tim and I barely knew each other. We had a common goal for the time we were together, but how to maneuver and achieve this, we had to figure out anew. How do we organize our new group? How far will we get? How do we make decisions? What do we do when it rains—cycle or look for cover?

On the first evening, we planned to camp at Lake Çıldır Gölü. We first passed the campground by mistake and ended up at another run-down picnic place with a burned-down restaurant and a security guard looking at us from a window. It was already getting dark, and as we tried to figure out what to do, Tim and I were hungry and wanted food—now. Thomas always sets up his tent and showers before having dinner (although sometimes he has a Snickers as an appetizer in the shower). But two hungry companions were one more than he was used to, so we ended up cycling back and having dinner (a fish each and some salad, the only option on the nonexistent menu) before setting up our tents. This was a measure I did not give much thought to until it was abruptly brought to my attention that after more than 500 days of cycle touring, this was an absolute (and unpleasant) novelty for Thomas.

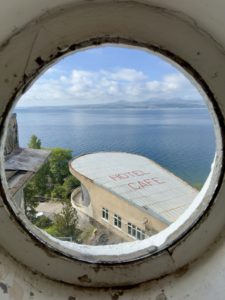

How to get enough (good) food has by now become a constant concern in my mind—sometimes more present, sometimes less. After crossing the border into Georgia, this worry extended to how to get food without local currency. We thought we would easily get money after the border because the towns looked similarly sized on the map to those we had passed in Turkey, and the ones in Turkey all had supermarkets and ATMs. Not so in Georgia… These similarly sized towns we passed were merely collections of rather simple homes—no supermarkets, no ATMs, no exchange offices. Luckily, we still had food for a day, and on the second day, we reached Vardzia. Thanks to its old, several-stories-high cave monastery, Vardzia was touristic enough to have a restaurant accepting cards—though not the hotel, which at least took our Euros.

The next day, we bunkered takeaway food from the card-accepting restaurant, which got us to the next bigger town with an ATM without going hungry but did not allow for a stop at the public bathroom. The sign in front of the public bathroom wanted “only 1 Lari” (30 Euro cents), and I couldn’t bring myself to squeeze through the turnstile without paying. Despite having at least seven different bank cards and a good amount of Euros and Dollars in our bags, I felt broke. So, there was some relief when we were finally able to withdraw Lari, or “Lari Fari,” as we started calling the Georgian money within our group. The name “Lari Fari” mainly arose as a mnemonic bridge, but it stuck—or maybe it was just our way of minimizing it, the way people sometimes do when they secretly want something but don’t have it and don’t want to admit that they actually do want it…

The highest point of Georgia, both geographically and emotionally for me, was our two-day hike to the Alti hut at the foot of Mount Kazbegi in the Caucasus. We left our bicycles in Tbilisi and took a shared marshrutka to reach Stepantsminda in the north, close to the Russian border, because it is a dead end and our route would continue further southward from Tbilisi afterwards. Beautifully located on a hill above Stepantsminda is the Trinity Church, which has become a symbol of Georgia due to its impressive mountain scenery. Most people take a taxi up to the church or walk up the hill behind it, but we went further up all the way to the Alti hut, which is modeled on Swiss SAC huts, and to the glacier that started a short walk above the hut. I felt incredibly good and alive hiking up that mountain, being amidst mountains. I felt so at peace in these surroundings, with the greatest conviction that I belonged there, that I didn’t even notice that I was the only female guest in the hut—until it was pointed out to me the next morning.

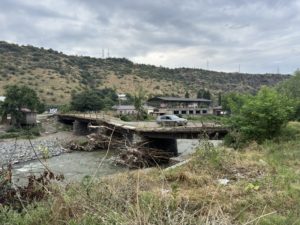

Back on our bikes again, we headed southward to Armenia. We were making good progress and cycled more and more behind each other instead of next to each other, partly adapting to the street conditions and the increased traffic, partly for efficiency, and partly because our initially seemingly endless pool of conversation topics slowly ceased. Of course, our surroundings still provided us with a good amount of food for conversations: ancient churches on top of hills, dilapidated infrastructure, desolately fixed bridges, many washed-out roads from the flood that hit the Debed River in spring, and finding food without “not-Lari” (Armenian currency). The hills towards Dilijan were green, and the weather was foggy and sometimes rainy—high-performance weather, as Tim called it—before the landscape became suddenly dry and the temperature rose towards Yerevan.

After successfully going through all the stages of team development and making it to Yerevan, it was time to say goodbye. I very much enjoyed the new impulses Tim brought to our journey, his fresh perspective and joy for new experiences—trying every unknown dish on the menu and picking the most exotic-looking drinks in the beverage display.

Apparently, Tim liked it with us too and couldn’t say farewell all at once either: We waved goodbye, seeing him drive away in the taxi to the airport with all his luggage and a huge box containing the bicycle in the evening, just to have him join us again for breakfast the next morning. I was sorry to hear that he had spent half the night at the airport only to have his flight delayed by 25 hours and finally being rebooked to another flight later the next night. But overall, I was happy to see Tim again and spend one more day together. Exploring a rundown Soviet “children’s” railway and watching Thomas and Tim discuss the mechanics of those old locomotives felt like the icing on the cake.

Anecdotes

Cycling through Georgia and Armenia felt like a bit of a detour back to Europe—at least in the big cities of Tbilisi and Yerevan. Indeed, we had never seen as many EU flags anywhere before as in Georgia. We enjoyed the many coffee shops that rated very high on our invented cappuccino and toilet score, and the pastries that came with the cappuccino. While I do feel some ambivalence about enjoying things that feel familiar and “similar to home,” it also simply felt good to be able to replenish ourselves in the big city bubble before heading out again towards less known and more foreign lands.

Ninotsminda/Georgia: We stayed the night with Warm Showers (a couch-surfing service for cyclists) together with another cyclist. The Russian couple hosting us had left Russia when the war in Ukraine started, and they are now trying to go to the U.S. before their passports expire in 10 years. They both work in tech, as do many of the Russians who have recently come to Georgia or Armenia. We were not the only ones being hosted by them that night; there was also a horse and its owner in the courtyard. The owner slept in a tent while the horse grazed in the grass behind the house. The next morning, the man traveling with the horse also came inside and started working on his laptop. What a surprise!

Country of Dust: I love to listen to an audiobook of a story connected to the land we are cycling through, as it gives insights into how people live, think, and feel here. It isn’t always easy to find such an audiobook for every country, and I hadn’t found one for Armenia so far. But then we met the producers of the podcast “The Country of Dust” in a hotel in Dilijan. They offered us Armenian coffee, and we started talking. They told us about their podcast project, where they try to depict Armenia today to the Armenian diaspora through individual stories from people somehow connected to recent Armenian history.

Their podcast might not be exactly a neutral documentary of the past few years, but listening to it on my bicycle in the days that followed, I got a much deeper sense of how Armenians feel about their country, the revolution, and recent wars, and it touched me deeply. Walking through Yerevan some days later, we randomly met one of them again. He stopped in front of us on the street and called out, “Aren’t you the cyclists from Dilijan?!”

Leave a Reply